Independent in Name, Dependent in Appointments: The New INEC Chair and the Questions of Transparency and Trust

The appointment of Nigeria’s new Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) chairman has once again exposed a familiar pattern in the country’s governance, one where secrecy, speculation, and executive discretion overshadow transparency and merit. While public attention briefly focused on the personality of the new appointee, the real issue lies in the opaque process that led to his appointment. Nigerians are not just asking who the new chairman is, but how he was chosen and what that means for the credibility of an institution that sits at the heart of the democratic process.

For decades, the appointment of INEC chairmen has carried political undertones, shaped more by presidential prerogative than by institutional independence. Each administration has repeated the same ritual of quiet selection, public announcement, and divided reaction. The outcome is predictable: renewed doubts about neutrality, confidence, and the integrity of the election process itself. As an analyst remarked, “The controversy is not about the individual but about the process.” What criteria guided this appointment? Was there an open, competitive vetting process? Or does the tradition of closed-door nominations continue under a new name? In a democracy struggling to convince its citizens of fairness, the opacity surrounding INEC’s leadership selections remains one of its most enduring contradictions.

A Historical Look at INEC’s Leadership

Since 1959, Nigeria has had six different electoral management bodies and fourteen substantive chairmen, with two women serving briefly in acting capacities. From the colonial-era Electoral Commission of Nigeria (ECN) to today’s Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), the evolution of leadership has reflected not only Nigeria’s shifting political order but also its persistent struggle to balance expertise, independence, inclusivity, and executive control.

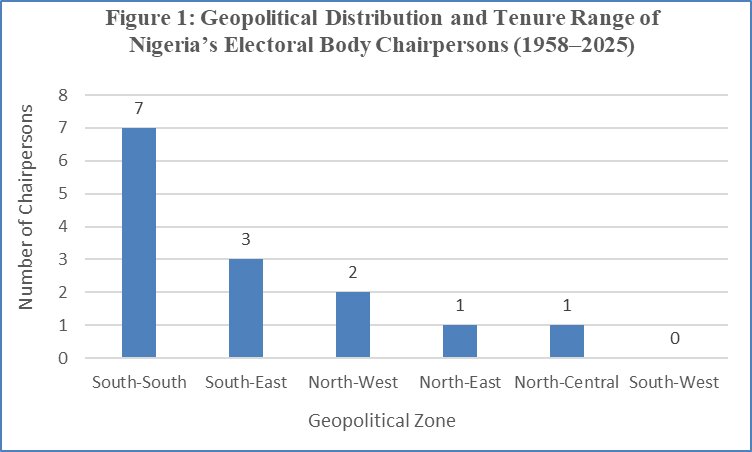

A geopolitical review of appointments reveals deep imbalances. The South-South has produced seven chairmen, followed by the South-East with three, the North-West with two, and the North-East with one. Until 2025, neither the North-Central nor the South-West zones had ever produced a chairperson. The recent appointment of Professor Joash Ojo Amupitan, SAN, from Kogi State (North Central), therefore, fills a long-standing regional gap.

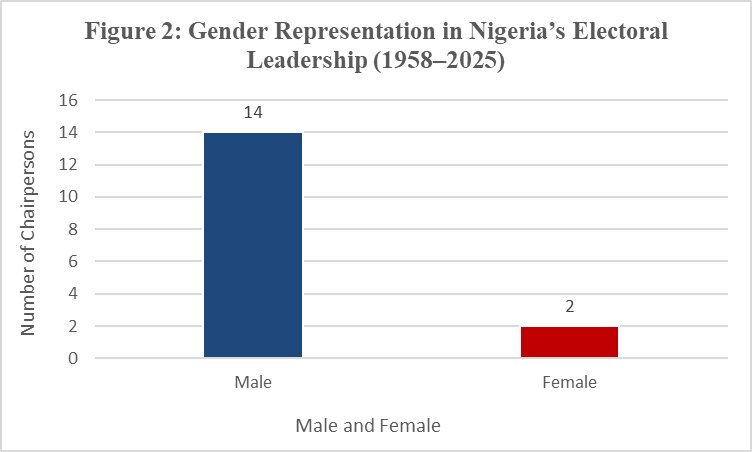

Yet, the more fundamental issue of inclusivity remains unresolved, particularly in gender representation. In Nigeria’s six decades of electoral administration, no woman has ever been appointed substantive chair. Only two women, Amina Bala Zakari from Jigawa State (North-West), who served in an acting capacity from July to November 2015, and May Agbamuche-Mbu from Delta State (South-South), who has been serving as Acting Chair since October 7, 2025, pending the Senate confirmation of Professor Joash Ojo Amupitan, SAN, have ever led the Commission and both in transitional capacities. This limited representation underscores how gender inclusivity remains more rhetorical than institutional in Nigeria’s governance architecture.

From Ronald Edward Wraith (1958) to Professor Joash Ojo Amupitan, SAN (2025), Nigeria's electoral leadership reflects its political evolution. Eyo Ita Esua (1964–1966) managed contentious elections, deepening instability. Michael Ani (1976–1979) oversaw the transition to the Second Republic, succeeded by Victor Ovie-Whisky (1980–1983), whose tenure ended with the 1983 coup. Eme Awa (1987–1989) and Humphrey Nwosu (1989–1993) led the Babangida transition, with Nwosu’s 1993 presidential election widely regarded as Nigeria’s freest annulled. The short tenures of Uya (1993) and Dagogo-Jack (1994–1998) reflected the turbulence of the Abacha era. Justice Ephraim Akpata (1998–2000) managed the 1999 transition, restoring civilian rule.

In the Fourth Republic, executive dominance persisted: Guobadia (2000–2005) oversaw the flawed 2003 elections, Iwu (2005–2010) presided over the discredited 2007 polls, and Jega (2010–2015) introduced reforms, including the introduction of the Smart Card Reader. After Jega, Amina Bala Zakari briefly served as INEC Chair before Buhari appointed Mahmood Yakubu (2015–2025), who expanded the use of technology, including BVAS and IReV. However, the 2019 and 2023 elections raised concerns about credibility. Yakubu’s exit led to the appointment of Acting Chair May Agbamuche-Mbu, who briefly served before President Tinubu appointed Professor Joash Ojo Amupitan, SAN, on October 9, 2025.

Theoretical Vs Operational Demands

The appointment of the new INEC chairman reinforces Nigeria’s recurring tendency to prioritise academic prestige over institutional experience. President Bola Ahmed Tinubu had an opportunity to break this cycle, as May Agbamuche-Mbu, who succeeded Mahmood Yakubu in an acting capacity, is the longest-serving INEC commissioner, having served from 2016 to 2025. She has been part of multiple electoral cycles, including the 2019 and 2023 general elections, working closely with Yakubu throughout his tenure. She could have been in the best position to continue the electoral reforms Yakubu was pursuing, especially since she was involved in the 2022 Electoral Act process and all its innovations. Moreover, it was a rare opportunity to make history as the first president to appoint a woman as the substantive chairman. If not for anything, there may have been a clear opportunity to test her strategies with the upcoming Anambra elections. However, this could not happen as Tinubu followed the familiar line of appointing a professor and someone who has been outside of INEC’s operations.

This is not to suggest Amupitan has not been studying INEC. However, the institution extends beyond the intrigues of an academic seminar room; it is a politically charged arena where decisions must balance the competing interests of parties, security agencies, and citizens. Managing elections requires not only technical expertise but also political sensitivity, strategic communication, and on-the-ground awareness. The persistent preference for legal technocrats and professors of political science overlooks the fact that, beyond understanding governance generally, elections are a complex logistical contest that demands tact, strategy, and experience.

Therefore, there are fundamental questions that must be asked when recruiting an INEC chairman: What do we want for our elections? Should we appoint someone who has never managed an election before to oversee a national election management body, or how many polls should you have managed before you can be an INEC chairman? What if you stand out first by being the chairman of a state electoral commission or a serving INEC commissioner? Have they served as a returning officer before, and what controversies have surrounded the elections they have overseen?

Holistically, when discussing the INEC Chairman, it is limiting to focus solely on his academic credentials without considering his past contributions to the democratic process, especially to elections. If he has none, it is troubling. The new appointment has therefore rekindled familiar expectations and frustrations. Nigerians are cautiously optimistic but remain sceptical, having witnessed similar transitions wrapped in reformist language yet constrained by old habits.

Quick Tests for INEC’s New Chairman

Despite the trust gaps he faced, Mahmood Yakubu introduced the 2022 Electoral Act, and some believe he was eager to make last-minute reforms to salvage his reputation. Unfortunately, he could not succeed; it now falls to the new INEC chairman to implement these reforms if he wishes to be seen as impartial and free from politics. The first major reform would be strengthening the INEC Results Viewing Portal (IReV), designed to improve transparency in Nigeria’s elections by enabling the public to access polling unit result sheets in real-time. The legal decisions following the IReV glitch in uploading the presidential result demonstrated that the use of IReV was optional. This emphasised the urgent need to reform the legal framework to make the use of IReV mandatory, ensuring election results are available in real time, verifiable, and legally supported, while also addressing issues related to infrastructure and operational capacity weaknesses.

Other reforms, such as phasing out Permanent Voter Cards (PVCs) in favour of digital slips, aim to cut costs, reduce disenfranchisement, and combat card-related fraud, but they require a quick rollout. Diaspora voting is a historic step, yet it needs legislative and operational support to succeed. Early voting for election workers could improve logistics and should be prioritised. Establishing an Electoral Offences Tribunal and a Political Party Regulatory Agency is essential for dispute resolution and enforcement of regulations. Additionally, reforms are necessary for marginalised groups, along with initiatives to clean the voters' register. At a time when it is perceived that the ruling party has weakened the opposition, the new INEC chairman should not abandon the process of registering the political associations seeking to become political parties. Fundamentally, the new INEC Chairman should pursue reforms that will ensure REC and future Chairmen of the Commission have a clear appointment process independent of the presidency.

Looking ahead, the off-cycle governorship elections in Anambra, Ekiti, and Osun offer the next INEC Chairman, Amupitan, an immediate opportunity to demonstrate commitment to these reforms. Managing these elections with transparency, credibility, and operational efficiency will shape Nigerians' trust in INEC ahead of the critical 2027 general elections.

Conclusion

For Nigeria’s democracy to progress, transparency, merit, and inclusion must replace secrecy and routine practices. A credible INEC cannot rely solely on personalities; it must be built on processes that foster trust before, during, and after elections. Restoring that confidence will require structural reforms that open appointments, promote diverse leadership, and make accountability unavoidable. Until then, each new appointment will remain a symbol not of renewal but of a democracy still striving to regain its people’s trust. The actual test of Amupitan’s appointment lies not in his credentials but in his ability to bridge INEC’s ongoing gaps between rhetoric and performance, technology and trust, inclusion and hierarchy.